From their first moments of preparation for the profession, screenwriters are ingrained with the imperative that they need to be smarter than anybody else on the project. Not more intelligent, or more knowledgeable with respect to all of the talents that must be gathered and exercised to execute their vision. But smarter in the context of knowing every beat of their screenplay backwards.

A good screenwriter makes certain that all the loose plot threads are neatly tied before the final frame. He or she knows what motivates each and every one of the characters, their back story and why they behave the way they do. No matter what twists and turns take place during the story, they all must have a basis in the internal logic of the piece.

When a script works, it purrs like a finely tuned Jaguar, effortlessly taking the reader (and eventually the viewer) on a smooth and exhilarating ride, where they never feel a single pebble on the road and are barely aware of the G-forces while gliding through the turns or accelerating along the final straight.

To this end, the writer is often assisted by others connected to the project, the development execs, a caring producer and energetic director, a cast anxious to breath life into the personalities that will enact the story, a conscientious crew ensuring that nothing intrudes on the manufactured reality.

The point of this entire, often lengthy and expensive process is to both ensure that the set never stalls or the audience never disrupts their suspension of disbelief to utter, “Hey, wait a minute, how does he know that, why is she acting so strange or that doesn’t work”.

As veteran screenwriter Frank Pierson observed in a famous lecture on adaptation, “Novelists can lie. Screenwriters have no such luxury.”

Yes, we writers are the guardians of “the word”. No film could be a success without our dedication to our craft…

And…

…what a load of shit!

You want to make a film a success? Blow something up and make it seem important.

This weekend, I went to a warehouse sale where the DVDs were 6 for $10. It wasn’t some pirate outfit. It was a guy who buys up the shelves of mom and pop video stores that have gone broke, manufacturers overstock and the like. Sorting through massive piles of films I’ve never even heard of was a humbling experience.

There’s so much out there that people sweated over, agonized to realize and struggled to make logical and understandable and --- perfect. And amid such an abundance of unfathomable effort were also titles that had made a boat load of money. Among these were two that eventually comprised the program of my semi-regular Sunday night double feature -- “Miami Vice – The Unrated Director’s Edition” and “Transformers”.

“Transformers” first.

Sometimes, I don’t get the point of something --- ukulele music, #followfriday, the Snuggie…

And. I. Just. Will. Never. Get. Michael. Bay. Hollywood’s Summer Blockbuster security blanket.

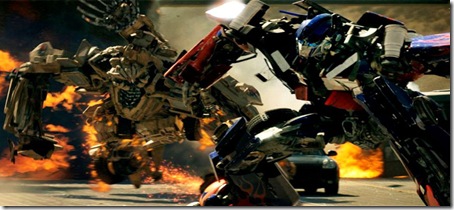

Michael Bay movies are mostly incoherent. They’re sprawling and stupid and don’t follow even their own fractured internal logic. There’s no character development. No story. Nothing to care about. Nothing to attach to --- because it’s all just eventually going to blow up. Loudly.

Need a character to do something completely out of character, the characters in Michael Bay films just do whatever comes into his head. Plot getting too convoluted to understand, ignore it and move on. Special effect not working, just interrupt it with a close-up of a simpering star (male or female) and keep going. Flow and transition don’t matter, just keeping throwing shit at the screen until you can’t make head or tail of anything because so much has already been irrationally stuck onto so much else.

Bay’s are movies that communicate one message – stop caring. Give yourself over to the kind of rush you can have without also expecting to feel something.

But no matter the utter pointlessness, “Transformers” earned just under $1 Billion at the box office, as did “Transformers 2” which will surpass the original’s take when it’s released on DVD shortly. That’s five times what each of the movies cost to make, meaning a third, fourth and fifth instalment are a foregone conclusion.

In other words, films that break all the rules of the filmmakers art will earn many times more than most of the most successful movies in history. And an easy Billion apiece more than all the films produced in Canada this year will show as profit.

Hell, Bay’s studio will make more money from posters featuring Megan Fox’s ass than the total that Telefilm will realize for investing in Canadian movies.

What does this tell us?

Well, it pretty much proves that this whole “develop to perfection” process we’ve evolved is one grand waste of time as far as a significant portion of the ticket buying audience is concerned.

They simply don’t care that a large number of people, who work for studios, production companies, agencies and the like, are charged with the responsibility of finding good and/or marketable material that will be what the audience wants to see in six months, nine months, one year or even two years time.

These execs flood out of Yale and Harvard and the film departments of USC and UCLA with degrees in literature and commerce and course credits for semiotics and Late 20th Century Romanian film. These are really, really intelligent people, the kind of people who can hear ten words of your pitch and know it’s a rework of a never published Danish folk-tale or a subject tackled better in a masterpiece by some obscure Russian Auteur.

If they like your idea, they know how to perfectly pitch it up the ladder to the next level of executives and the level above that and the one even further above that. And once an idea is sold, they may or may not be among the vast cc: list that will then append notes, rethink plot points, spit-ball casting and do all of the other things that comprise the ascending levels of Development Hell.

Draped in the finery sold by Fred Segal and Barney’s, they book tables for breakfast, lunch and dinner in every trendy cafe from Santa Monica to Burbank, massively fuelling the local economy.

And Michael Bay renders all that they do pointless.

He knows that the secret is to stop making sense, to set aside the intellectual games and just blast whatever is in front of the camera to smithereens.

In “Adventures in the Screen Trade”, writer William Goldman suspects that no studio executive ever goes home and says “Guess what, Honey, we decided to make ‘Mega Force’!”. Yet somewhere in LA, there always seems to be a guy ecstatically screaming “We hired Michael Bay!” through his Bluetooth.

And if you don’t think the studios haven’t finally realized the secret to his Midas touch, take a gander at what’s on the production slates for next summer and beyond. Back in July, Universal won a FOUR STUDIO BIDDING WAR for the rights to the Atari video game “Asteroids”. You remember Asteroids, the only thing that happened during the entire game was --- shit blew up.

Also looking for writers who couldn’t give a crap about character, plot or nuance are: “Mechwarrior”, “Shadow of the Colossus”, “World of Warcraft”, “Infamous” and “Diablo” --- games that are repetitive and predictable and don’t do much but make stuff explode.

Seeking an antidote to the nihilistic future predicted for my profession by “Transformers”, I plugged the “Miami Vice” disk in the player. I’d seen the movie in a theatre and had liked it, adored the score and had been enthralled by Michael Mann’s always muscular imagery.

Michael Mann has produced and/or directed and/or written some of the finest films I’ve had the pleasure to experience, from “Thief” to “Manhunter” to “Last of the Mohicans” to “The Insider” to “Collateral” to his masterpiece “Heat”. They just don’t come any better and brighter than Michael Mann.

So I figured, “Hey, you’ve already seen the movie, switch on the director’s commentary and get some insight into the kind of genius that might save us from an endless parade of Michael Bays”. So I switched on the commentary. And I listened. And I was amazed --- in a kind of “You must be fucking kidding me” way.

For as the movie rolled, Michael Mann talks not about filmmaking, but about hardware. He goes on and on about the engineering genius of those who build “Go-fast” boats or one of a kind airplanes, while practically disassembling and putting back together every piece of weaponry that appears on camera.

He prattles on about how this actor is a genius and that one’s brilliant, in the process suggesting that, for the most part, fairly stock performances have a special quality because the actress is really British but you can’t tell or only speaks Mandarin so she had to learn her role phonetically or absolutely floored him with their performance in some arcane Bolivian art film.

He details the back stories he constructed for many of the characters, how their parents were Cuban doctors who fought in Angola for example, when that information has nothing to do with any scene in the film and is never reflected in anything the actor is doing either. Instead of revealing character through what they say, do or by what others say or do about them, Mann just spins off on fantasies that suggest he has a whole house full of imaginary friends.

Mann describes having his actors spend weeks with undercover drug squads, even participating in drug deals and drug busts to learn what it’s really like to be undercover, how they spent endless hours in SWAT training so they hold their guns perfectly and are aware of what the rest of the actors playing cops would be doing in the tactical situation being portrayed.

You almost wanted to scream at the screen, “They’re doing the same thing you can see any actor do who’s watched an episode of the original “Miami Vice” TV show!” while also wondering if having the actors follow Drug Bust Scenario # 23 saved him the trouble of actually having to block the scene.

Things began spiraling out of control as I realized Mann was not going to explain why the first two set pieces of the film, the opening boat race and following nightclub scene had virtually nothing to do with what followed beyond revealing that Crockett and Tubbs like women and driving fast.

He ignores major inconsistencies like how does Colin Farrell suddenly have a grenade after three guys just frisked him by concentrating instead on how the set was painted. And, perhaps worst of all, despite his apparent desire for absolute verisimilitude, he ignores the central story of Crockett breaking the cardinal rule of undercover and sleeping with the enemy. In fact, in the scene where that occurs, he launches into a lengthy history of Cuban Salsa.

By the time Mann went into detail about the dangers and difficulties of shooting location footage in Paraguay, which, beyond a stock shot of the Iguazu Falls, could have been a backlot in Culver City, I was wondering if his primary talent was spewing the kind of bullshit he’d obviously used to convince some dumb studio exec to pay for such a ridiculous additional expense.

And when he began painstakingly detailing the SWAT tactic strategy of the final gun battle with actors following a classic “L” shape attack plan, and all he’d learned from the neurosurgeons who’d been technical advisors on a brain surgery scene, I finally lost it.

Somehow a shipyard shootout as old as an episode of “Naked City” was being prettied up as something of major cinematic significance while also regurgitating medical mumbo-jumbo that had nothing to do with the 30 second hospital scene he’d actually shot.

The producer part of me considered how much it must have cost to insure Colin Farrell so he could go along on a drug bust and how much had been frankly wasted trucking a crew to Paraguay and the Dominican Republic and elsewhere for footage he once created for the original TV series without leaving Dade County.

Meanwhile, my writer incarnation was growing more confused by the mounds of research Mann had obviously acquired and then clearly not bothered to use in any way that might benefit his audience.

I’m sure the man is wonderful company over dinner and fills his production with fun toys and field trips. But none of that was making the movie richer for anybody watching it.

And I started to wonder if all of those honorable traits we screenwriters hold dear and the level of craft we sacrifice our personal lives and sanity to maintain really matter.

Maybe we need to just blow stuff up and bullshit about the rest of it. God knows it seems to be what really makes a movie successful.