I never made it to Woodstock.

I wanted to go. Everybody I knew did. I think my first awareness of it was a full page ad in an issue of Rolling Stone early in the summer of 1969. The line up of talent was awesome, unbelievable for somebody who lived in Regina and only got to see the odd top 40 artist like “Tommy James and the Shondells” or “The Turtles”. The thought of ever seeing Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin or The Who in concert was a distant dream, let alone the possibility of seeing them all, and many more, on the same weekend.

But a year later, I got to attend Woodstock and I’ve been back many times since, courtesy of Michael Wadleigh’s magnificent documentary.

The story of how “Woodstock” (the movie) came about is just about as fascinating as how the festival itself came into being.

In 1969, “Mike Wadley”, as he was often billed by the low budget producers who hired him as a cinematographer, was an Ohio filmmaker trying to crack the counterculture film scene in New York. But that crowd was hanging with Andy Warhol and none of Wadleigh’s “underground” films ever made a dime. But at some point he made the acquaintance of Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld, the primary visionaries behind the Woodstock Festival, and they agreed to let him film the concert.

Kornfeld approached Martin Weintraub, an executive at Warner Brothers, for a donation to the festival and came away with $100,000 in return for the distribution rights of any film that might result. Since Warners was nearly bankrupt at the time, Weintraub had to battle the other Warner execs finally putting his own job on the line before the company would cut the check.

But $100,000 wasn’t anywhere near what Wadleigh soon realized the massive event would cost to cover. So he went around the New York film community, finding 100 underground filmmakers, film students and out of work crew people, who would give him the weekend for free. In return, if the film succeeded, he promised to pay them double their normal rate.

Among those who signed on to edit the film were a couple of complete unknowns named Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorcese.

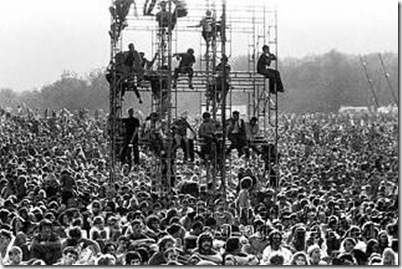

Wadleigh arrived at Woodstock (actually Bethel, NY) with his crew and 1000 cans of film. But instead of just shooting the acts on stage, he set several of his cameramen loose in the crowd and on the town of Bethel, documenting not only the “Hippies” attending the festival but the reactions of small town America.

Like those attending Woodstock, Wadleigh’s crew dealt with the torrential rains, the mud, the congestion and lack of food, water or even a place to relieve themselves, constantly recording everything that happened around them. The following week, he dumped 120 miles of exposed footage in the laps of Schoonmaker and Scorcese.

What resulted was not only the best concert film ever made, but an intelligent and artistic examination of a world in transition.

In backroom battles with Warners, Wadleigh managed to keep the performances they felt the audiences only wanted to see off screen for the first 23 minutes of his original 3 hour release cut. He knew that for the film to succeed, the scene had to be completely set for not only the music lovers Warners needed to immediately recoup their investment, but the millions more who needed to understand what Woodstock really meant and whose return visits could make the film a real success.

And those first 23 minutes before Richie Havens, a relative unknown at the time, takes the stage, remain as powerful today as they did back in 1970.

Although “Woodstock” went on to earn more than $50 million in its initial release (back when movies cost $2) and won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, Michael Wadleigh, once again, never made a dime. And while the later re-cuts and re-releases and the use of the footage he shot in his docs “Janis” and “Hendrix: Live at Woodstock” would finally earn him his financial due, he has only made one more feature film, 1981’s “Wolfen”, an inspired horror film years ahead of its time.

Twenty years after Woodstock, I met Richie Havens on a beach in the Caribbean. He was still touring (still is today) and still closing his concerts with “Freedom” the song made famous by the film. Havens didn’t really remember how Wadleigh and his crew went about covering his appearance that day, overwhelmed as he was by the moment and what it meant to someone of the Peace, Love and Groovy generation.

“You need to understand what it meant,” Havens said, “I looked down at that crowd from the helicopter bringing us in. All those people standing against the War and the darkness and the rigidness of the society. For the first time, you could see that we were winning.”

Here then are those opening moments of “Woodstock” followed by my favorite sequence of the film. Everything here has been copied a thousand times by now and evolved in a million different directions by ten million different artists. But this was the first time -- in one film – made by a handful of gifted people.

Peace. Love and Far-out, man.

Enjoy your Sunday.