To be sure there is usually one overriding creative vision at work, a vision that is served by the others. Whether that vision is embodied in the script or born of a producer's take on the material, executing the vision ultimately falls on the shoulders of the director.

For the most part, I like directors. I can count on one hand the ones I've worked with and would never want to work with again. The good ones bring things to a script or a performance that you never imagined were there. The mediocre ones still break your heart with the effort they make to get one last shot before the sun comes up and ends their night shoot. Even the ones who think actors are cattle remain employable by realizing they still have to feed them well, milk them regularly and yodel when the sun goes down so they won't stampede.

The producer who taught me most of what I know about television used to say, "I always get worried when I walk onto a set and I know which one's the director." And he was right.

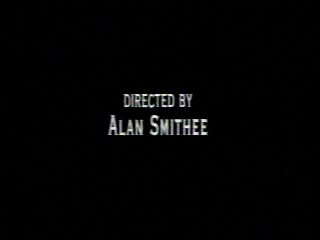

Directors should know better than anyone else that we're all in this together. So it constantly amazes me that so many directors still support such charades as the possessory credit, the auteur theory and the "Directed by Alan Smithee" pseudonym.

Flatly, there's no such thing as the possessory "A Film By ----" unless one guy did everything including being all he pointed the camera at. Any director taking a possessory credit is letting everyone else know how little he actually values their contribution. If you need the money, go ahead and work with somebody like that. If you value who you are and what you do -- don't. Filmmaking is leaving egos at the door, not exhalting one of us above all others.

Likewise the "auteur theory" -- that quaint Cahiers Du Cinema/Andrew Sarris invention that insists that a film reflects the unique personal vision of the director and no one else.

I used to carry around a script I wrote called "The Auteur Theory". It was 120 blank pages. "There you go, Sparky -- shoot that!"

And finally, there's the institutionalized nom de guerre that all directors must take if they don't want their name on a film, "Alan Smithee"; a name that concludes the credits with the silent promise that what you are about to see is going to be complete crap, because Alan only puts his name on films that were mangled beyond all Director tolerance.

Writers often take pseudonyms when they're unhappy with their work. I've done it a couple of times myself. Writers have far less control over the finished product, so when your race of intelligent aliens suddenly morphs into bikini wearing bimbos dispatching their enemies with lead pipes, you want people to know exactly how "Tobias House" spent the script fee.

Most often you end up with a nom de plume that won't make the few people actually reading the credits think they should ask for a refund. But there are books on "Alan Smithee" full of tales of the idiots or the system that wounded some poor director and his perfect vision so deeply that his only recourse was to encourage all us in-the-know film folk to silently cheer our Hollywood rebel for stickin' it to the man...

I used to pump my fist along with them. Now I'm one of the Alan Smithee bad guys. Only thing is -- I know what really happened...

My Alan Smithee film was a US network MOW with two fairly famous and quite talented leading actors, a very good script and a tight shooting schedule and budget. We needed a director who understood the material and could shoot fast. And we found him. I liked the guy from the start. He didn't want any script changes, was excited by his stars and understood that a half dozen of the shoot days would be production nightmares. But he went right to work story boarding those days and sharing his enthusiasm for the job at hand.

As those of you who have been watching "Studio 60" may suspect, as I do, that Aaron Sorkin patterned the Danny Tripp character after me, right down to my "How much do I need to know about this..." catch phrase -- my producing theory is simple, "Hire good people and leave them alone." And since we were shooting two films back to back, I was more than happy to give this guy his head...

For about a day.

His first order of business had been to cast the villain of the piece and a number of day players. Having been an actor, I find casting sessions difficult. I always want to help the actors out. That undercuts the Casting Director and the Director, so I usually look at tapes of the first sessions, add people to the callbacks if I think they might improve and try to be on my best behavior for the second round.

I got back from the shooting set as the Casting Director walked in with the tape. My incredibly efficient director had burned through the session in record time, already made his selections and left for dinner. The Casting Director felt I needed to see the tape. It was interesting all right.

Most of the actors auditioning for single scene parts never completed the short sides they were given before being thanked politely and escorted out -- and every single selected performer was visibly on the heavy side. When I got hold of the director, 4 hours later, highly recommending his cafe of choice and their exceptional wine list; he acknowledged that he wanted "fat actors". He believed audiences wanted to see people like themselves onscreen. I pointed out that slim people watched TV too. He insisted his vision would work.

His choice for the villain was an actor who had not been asked to audition. He was a guy notoriously difficult to work with and whose talent didn't always justify the trouble. On a difficult shoot, he could be an added headache.

Having been through some network casting wars on the film already shooting, I knew his approach could be problematic. I suggested we look at the tape together in the morning and find a list of performers we both could live with.

He arrived next day happy to have whatever cast I wanted as long as he got his villain. When his actor of choice turned us down, he washed his hands of casting altogether, insisting he would be happy to work with whatever talent graced his set.

My biggest flaw is that I take people at their word. If you tell me you're happy, I assume you are. Tell me you're not, I'll see if we can find a solution. Through the rest of prep, the man was affable and charming. He loved the set designs, adored the costumes, thought the cinematographer was the best he'd ever worked with. I was growing confused. I knew I hired good people -- I'd just never hired anybody who was perfect, let alone a whole crew of them.

His storyboards convinced me we were in trouble. They were all over the place. He blamed the artist. The kid didn't understand what he'd been describing. It would be fine on the day. He knew what he wanted.

But I didn't, and neither did the AD's. When I asked him to break down the script with them so everybody understood what was expected, I was off his Christmas card list.

But the first days of shooting went well. We weren't going into overtime and the footage looked good. Some of it felt a little by the numbers but it was by the numbers stuff and any time and energy we banked now would help when we got into the tougher days ahead.

But script timings began coming in short, meaning the 90 minute film we were making was going to end up at 88, then 86. I added back a scene I hadn't wanted to cut in the first place. Then added another to 2nd unit and told the stunt team to enhance the car chase.

But as we passed the midpoint of shooting, we were still by the numbers and I knew he was just phoning it in. I made an appointment to talk privately. He blamed the cast, had problems with the crew too. Everybody was letting him down.

He was full of shit and I called him on it. I was expecting an argument but all I got was a smile. He was sorry I wasn't happy. He would try to do better.

But he didn't and there wasn't the time or money to replace him. We wrapped and he delivered his cut -- 8 minutes short. Included were angles and takes so inappropriate they had me doubting the editor's sanity. Her rough cuts had improved on the dailies and avoided all the problems I was now seeing. But it was his cut. She had no choice but to deliver the unwatchable mess that was his vision.

I phoned to ask if he could explain some of the choices. He didn't see the need. Even though he didn't have final cut, he believed his version was terrific and 8 minutes short was just something the network would live with.

We couldn't shoot anything additional, so the editor and I spent a week rebuilding what we had into a 90 minute final cut the network loved. This version would go on to garner better ratings than had been expected and receive unanimously positive reviews. But he dubbed it an Alan Smithee film.

My editor cried. The actors were insulted and the network incensed. I tried reasoning with the guy, assuming his problem was with me. He was shocked I would suggest such a thing. He'd had a wonderful time, hoped we could work together again. We just didn't "get" what he was trying to do and he couldn't put his name on the version we were happy with.

I tried to understand how he felt, but I couldn't shake how he'd said it with such glee.

The Director's Guild mandates Alan Smithee as the replacement credit for any director wanting to take his or her name off a film. I'm sure there's a fair and logical reason for doing that. But I'm also sure there's a hint of vindictiveness behind it, a quiet reminder to the rest of us of where the true vision behind a film is supposed to belong.

Interestly, Hollywood's best known Director rebel, Sam Peckinpah, a man pole-axed repeatedly by the studio system, kept his own name on such brutalized works as "Major Dundee" and "Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia". A number of times, friends suggested he let "Alan Smithee" take the credit. Sam always refused. If he lost, so be it. But he wouldn't let anybody forget who'd fought the battle.